Weatherburn

You can download a PDF version of this article here

The value of any policy depends on the purpose to which it is put. Prohibition can be made to serve at least three distinct purposes:

* to reduce the prevalence of illegal drugs;

* to reduce the quality of drugs consumed; or

* to reduce the harm associated with illegal drugs.

The overarching goal of Australian drug policy is harm minimisation. That is what I am going to focus on tonight.

The theory underpinning prohibition

First I am going to discuss the theory underpinning prohibition – the ways in which prohibition might be expected to reduce drug-related harm. Then I am going to discuss the arguments which have been raised against that theory. Finally, I am going to say a few words about the idea that the goal of drug policy ought to be to minimise drug-related harm.

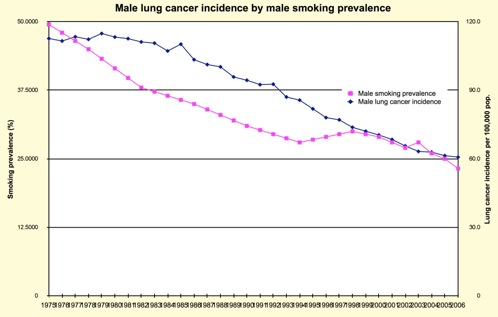

Let’s begin with the question of how prohibition might be expected to reduce drug-related harm. Although harm reduction is often contrasted with use reduction, there is actually a close relationship between drug consumption and drug-related harm. This graph, plotting the incidence of lung cancer among males against the prevalence of male smoking, illustrates the point.

One obvious way to reduce drug-related harm then is to reduce illicit drug consumption. It is argued, not necessarily by me, that prohibition could be said to achieve this objective in four distinct ways:

1. declaring drug use criminal might help reinforce social norms against the use of drugs like cannabis, heroin and cocaine;

2. the formal and informal sanctions accompanying convictions for drug use might act as a specific deterrent to further drug use by the person sanctioned and/or as a general deterrence to anyone contemplating the use of illegal drugs;

3. prohibition might act to reduce consumption through its effects on the non-monetary costs associated with drug use – including the time and effort involved in finding a dealer, the hassles associated with police and courts, the risks of infection and overdose and the risk of being ripped off or assaulted; and

4. prohibition could be said to suppress consumption through its effects on the price of illegal drugs – drug producers, importers and distributors, like insurance companies, compensate themselves for the risks they take by demanding higher premiums. These are passed on to consumers in the form of higher prices, and, as with every commodity, higher prices usually mean lower levels of consumption.

The two sets of objection to these theories

Let’s now turn to the objections raised against these theories. I split them into two categories. Arguments in category A challenge the four defences of prohibition which I have just outlined. Category B arguments challenge the underlying assumption that reducing consumption reduces drug-related harm.

‘Prohibition has failed’

Perhaps the most frequently heard objection to the social norm and deterrence arguments is that prohibition has failed. The vast sums of money spent on drug law enforcement haven’t discouraged people from using illegal drugs. In the last year, for example, more than one in ten Australians over the age of thirteen used an illegal drug. Thirty-eight percent have tried an illicit drug at some stage in their lives. [2007 National Health Strategy Household Survey, pp.4-6]

The problem with this argument is that, for all we know, illegal drug use might have been even higher but for the effect of prohibition. If we want to know whether prohibition constrains consumption, we need to know what would happen to drug use in the absence of prohibition.

Most of this evidence comes from studies of the effects of cannabis decriminalisation. Eric Single is perhaps the most frequently cited reviewer of this evidence. He examined trends in cannabis use in 11 states in the United States in which criminal penalties for the use and possession of small amounts of cannabis were removed back in the early 1970s. Broadly speaking, he found no differences in cannabis use trends between states which prohibited and states which did not prohibit the use and possession of cannabis. Johnson, O’Malley and Bachman found similar results in studies of US high schools students.

Australian evidence is similar. In 1987, the South Australian Government introduced a cannabis expiation scheme under which those caught using or possessing small amounts of cannabis were given an infringement notice and a fine, rather than being subjected to arrest and prosecution. Donnelly, Hall and Christie examined trends in the lifetime and weekly prevalence of cannabis use before and after the expiation scheme was introduced, comparing South Australia with other Australian states and territories. They found no significant difference between South Australia and the rest of Australia in the growth rate for weekly cannabis use. The prevalence of lifetime cannabis use increased significantly faster in South Australia than in the rest of Australia, but no faster than in some prohibition states such as Tasmania.

Problems with the evidence

Although the evidence overall seems to suggest that prohibition doesn’t have much effect on the prevalence of drug use, there are some important qualifications surrounding this conclusion.

Firstly, the relatively small sample size used in the National Drug Strategy surveys in the period immediately before and after cannabis law reforms in South Australia limited its capacity to detect changes in the frequency of cannabis use among dependent users. This is crucially important, because although dependent users represent only a small fraction of the total drug-using population, they account for a large percentage of the illicit drug consumption and drug-related harm.

Secondly, there are instances where decriminalisation has been accompanied by an increase in cannabis use. In 1976, the Dutch adopted a formal written policy of not enforcing the prohibition against cannabis sale or possession whenever the quantities of cannabis involved were 30 grams or less. Initially, the change had no effect on cannabis use. From the mid-1980s onwards, however, the number of Dutch coffee shops selling cannabis began to grow – and the prevalence of cannabis use with it, particularly among the young. These results have been interpreted by some, such as Peter Reuter, as evidence that, even if de-penalisation (ie removal of penal sanctions) doesn’t have much effect on cannabis consumption, de facto legalisation certainly does.

Does prohibition constrain non-monetary costs?

Let me turn now to the argument that prohibition constrains consumption through its effects on the non-monetary costs of illegal drug use. At first blush, this argument would seem highly implausible. After all, if the non-monetary costs of drug use discourage its use, we would expect heroin users to quit after just a few arrests. This obviously isn’t true, but perhaps the impact of prohibition is subtler than this.

In 2001, we asked a representative sample of 18 to 29-year-olds in NSW whether or not they would use more cannabis if it were legal. About 16% of those who had never used cannabis said they definitely or probably would. When we looked at weekly users of cannabis, more than 90% said they would. There is other evidence as well. When dependent users are asked why they were entering treatment, two of the factors most frequently cited were fear of prison and troubles with the courts and police. Studies of police crackdowns in open-air drug markets, such as one in Switzerland, sometimes find an increase in the rate of entry into treatment. Heroin users who have been hassled by police, arrested or imprisoned are far more likely to have entered methadone treatment than heroin users who have had only limited contact to that point with the criminal justice system.

These observations suggest that prohibition and drug law enforcement play an important role in encouraging users to enter treatment.

The argument that drug prices reduce illicit drug consumption

According to this argument, drug traffickers demand higher premiums to compensate themselves for the risks they take. These higher premiums are supposed to result in higher retail prices and lower levels of consumption. Two objections have been raised to this argument: that prohibition and law enforcement have little or no effect on street price; and that increasing the price has little or no effect on consumption.

In responding to the first objection, it is important to distinguish between the effects of illegality per se and the effects of intensified law enforcement. There is no doubt that banning the production, sale or use of a desired good greatly increases its value. The retail costs of drugs such as cannabis, heroin and cocaine far exceed the costs associated with their production and distribution.

I might be on unsafe ground here, in speaking of drugs with which I am not familiar, but pethidine, I am informed by my local pharmacy, is legally available for about $2 a hit. By comparison, a cap of heroin at Sydney will cost, at the moment, about $50. Even then, the heroin is only about 20% to 30% pure. Research in the United States suggests that the black market price of cocaine is between two-and-a-half and five times the price which would prevail if it were legalised, while the black market price of heroin is thought to be between eight and nineteen times higher than it would be in a legal market.

Prohibition does increase the cost of illegal drugs

This is not to say though that putting more money into law enforcement will increase the cost of illegal drugs still further. The evidence on this issue is mixed. A combination of the Turkish opium ban, the breaking of the French Connection case and Mexican opium eradication efforts in the 1970s are widely credited with greatly increasing the cost of heroin in the United States. On the other hand, cocaine prices in the US fell through the floor during the 1980s, even as investment in law enforcement went through the roof.

In 1995, we conducted an analysis of the effect of heroin seizures on the price, purity and availability of heroin in Cabramatta, then Australia’s largest open-air heroin market. We found no effect, and other studies have since found similar results. However, just as we began to reach the conclusion that law enforcement activity or intensified law enforcement activity had no effect on prices, the heroin shortage came along. In one month the purity-adjusted price of a gram of heroin in Sydney rose by 112%. The National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre, which studied the shortage, argued that it was caused in part by the efforts of Australian law enforcement agencies.

Not surprisingly, critics of prohibition disagreed. Some have argued that, since Vancouver experienced a heroin shortage around the same time as Australia, the Australian law enforcement agencies cannot be credited with producing the shortage. Others, Alex Wodak for example, have reached the same conclusion from evidence that heroin production in Burma began falling before the Australian heroin shortage began.

Neither of these arguments is very compelling. The change in heroin availability in Vancouver was nowhere near as severe nor as abrupt as the heroin shortage in Australia and also seems to have started considerably earlier. The claim that opium production in Burma fell before the heroin shortage began is only partly true. Opium production in Burma did fall between 1996 and 1999, but it rose again during the years in which the Australian heroin shortage began.

Price and consumption

Personally, I am not sure what caused the heroin shortage, but that is not the main issue. As long as prohibition makes drugs more expensive than they would otherwise be, the crucial question for policy is not whether or not police can push up the price, but whether or not higher prices lead to lower levels of consumption and drug-related harm. The available evidence suggests that they do, at least as far as consumption is concerned. Economists call the sensitivity of demand for a product to changes in its price its ‘price elasticity’.

An elasticity of -1 means that when the price of a commodity increases by 1%, demand falls by 1%. An elasticity of -0.2 means that a 1% increase in price causes demand for it to drop by 0.2 of 1%. If pushing up the price had little or no effect on consumption, we would expect its price elasticity to be zero or very small, but it isn’t. Tobacco, for example, is an addictive drug, yet the long-run price elasticity of demand for cigarettes is in the range of -0.27 to -0.79. Estimates of the price elasticity of demand for heroin and cocaine are more variable, but the mid-range of estimates for these drugs is around -0.95. Prohibition does constrain consumption and therewith some drug-related harms. What we don’t know is how big this effect is and whether or not the costs imposed by prohibition are worth the benefits it produces.

Does price increase reduce harm?

It is time then to deal with the objections in category B, that is, objections to the idea that if prohibition succeeds in pushing up prices, it will succeed in reducing drug-related harm.

The truth is obviously more complicated than this. When we prohibit a drug we inflict harm on those we prosecute for breaching the prohibition. If they are in prison and have children, we harm their families as well. Sometimes we harm their health. It is known, for example, that fear of arrest sometimes prompts a heroin user to share needles and inject too quickly, both of which are inimical to public health.

But that is not all. Because drugs are expensive, users frequently resort to crime to fund their addiction. Because dealing is profitable, people, including police, are drawn into organised crime.

Furthermore, as anyone who has watched Underbelly would know, because the principals of organised crime can’t resort to the civil courts to resolve their disputes, they often end up shooting each other and anyone else who gets in their way.

The ‘inelasticity’ of the demand for heroin

The critics of prohibition have another argument up their sleeves. When consumption of a product falls by less than 1% in response to a 1% increase in its price, economists say that the demand for the product is ‘price inelastic’. If demand for any drug is price inelastic, prohibition is in serious trouble. Suppose, purely hypothetically, that heroin costs $50 a cap and that 10 million caps are sold in NSW every year. Total annual expenditure would then be $500 million a year. Suppose further that a 1% increase in price produces only a 0.5 per cent fall in consumption. If we were to increase the price by 10%, to $55 a cap, annual consumption would fall from 10 million caps to 9.5 million; but here’s the rub – annual expenditure will rise, despite the falling consumption, from $500 million to $523 million. In other words, if demand for a drug is price inelastic, raising its price might only make things worse: users might end up committing more crime to fund their addiction, dealers might earn bigger profits and the incentives for corruption might increase. This is a powerful argument, but it clearly hinges on the assumption that demand for illicit drugs is price inelastic. So what does the evidence reveal?

It used to be thought that because addiction is sometimes described as a brain disease, dependent users will do anything and pay anything to get hold of the drug they need. This, as we have already seen, is false. Unfortunately, there is no agreed figure for the price inelasticity of demand for any illegal drug. Estimates of the price elasticity of demand for cocaine, for example, span a range of -0.6 to -2.5.

My view is that demand for most illegal drugs is price elastic

Why do I say this? Higher prices appear to reduce consumption and drug-related harm. Jonathon Caulkins, for example, found a close inverse relationship between the price of heroin and cocaine in the United States and emergency department admissions for heroin and cocaine overdoses. In fact, price changes accounted for nearly all the variation in emergency department admissions for these drugs.

The best evidence for price elasticity though comes from the Australian heroin shortage. Heroin is addictive. Yet, within two months of prices doubling, median weekly expenditure among users in Cabramatta fell by 36 per cent, from $550 a week to $350 a week. If demand for heroin were price inelastic, you would expect drug-related crime to increase. It didn’t. In the period leading up to the heroin shortage, robbery and theft offences were all rising. In the eight years after the heroin shortage, robbery rates fell by 38 per cent, burglary by 50 per cent, motor vehicle theft by 56 per cent and general theft by 37 per cent. Even after you control for other economic and social factors – a study which is on our web site – the heroin shortage had a big effect on crime, not just in NSW but in other states and territories as well. The fall in heroin consumption produced other notable benefits, including a 67% reduction in fatal and non-fatal opiate overdoses and a substantial reduction in notifications for Hepatitis-C.

It is really important to emphasise at this point that these benefits are not in any way contingent on the assumption that law enforcement caused the heroin shortage. You need only believe that prohibition keeps the price higher than it would otherwise be. In that event, prohibition keeps many of the harms associated with heroin lower than they would otherwise be.

Is prohibition the best way to minimise harm?

This brings me, finally, to the issue of harm minimisation. Recognising these facts, some have retreated to the position that prohibition might reduce some drug-related harms, but it is certainly not the best way to minimise drug-related harm.

There is a sense in which this is true and a sense in which it is false, or more accurately, it is metaphysical. It is true to say that prohibition and law enforcement aren’t the best way to reduce some drug-related harms. I am absolutely sure that the needle and syringe program has done more to reduce the spread of Hepatitis-C and HIV/AIDS than anything law enforcement has done or will ever do. However, if the claim is that prohibition is not the best way to minimise all drug-related harm, then I think the claim, like all metaphysical assertions, is completely untestable. Let me explain why.

Identifying, measuring and weighing harm

To know which of two or more policies better minimises drug-related harm, two conditions must be met. First, we need to be able to identify and measure the harms associated with each policy. Second, we need to agree on the weight to be assigned to these harms. Both requirements are difficult to meet. We have trouble measuring the quantity of drugs being consumed, let alone all the harms associated with consumption. Harms like overdoses might be easy to quantify, but what about the effects of use on public amenity or the effects of search laws on civil liberties – how do we measure them?

Comparison of alternative drug policies, using simulation models, is being attempted. The models achieve precision only by making questionable assumptions about the markets. Measurement, however, is not the biggest problem facing harm minimisation advocates. The biggest problem is that there is no agreement on which harms matter the most.

You might think that the key imperative in illicit drug policy is to protect public health. Someone running a shop in Cabramatta might think that the key imperative is to keep needles out of the park and drug users off the street. You might think that the loss of civil liberty entailed in police searches is worth the benefit in terms of public amenity. Others might think that it is not.

It is easy to say the goal of drug policy should be to minimise drug-related harm, but whose harm should we try to minimise and how do we compare qualitatively different types of harm? Is it possible to compare the harm done by injecting users when they discard their equipment in a public park with the harm done to them when

* police unfairly harass them;

* the fear of arrest prompts them to inject too quickly; or

* in a bid to avoid detection, they share injecting equipment?

If reducing the harm suffered by users increases the harm suffered by everyone else, whose interests should prevail? There is no scientific answer to these questions. They are political, not scientific.

Conclusion

There is nothing wrong with the idea that we should strive to reduce particular drug-related harms, such as crime, morbidity, mortality and drug-related problems of public amenity. We kid ourselves, though, if we think we can minimise all drug-related harm. Drug policy involves hard trade-offs between competing harm-reduction objectives. There is no such thing as a free lunch and there is no such thing as a drug policy which reduces one harm without increasing the risk of another.

*Delinquent-prone Communities and Law and Order in Australia: Rhetoric and Reality

About Weatherburn

Don Weatherburn BA, Ph.D is probably best known for his work on sentencing, drug law enforcement markets and the influence of economic factors on crime. He is the Director of the NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research in Sydney. He is a fellow of the Academy of Social Sciences in Australia and an Adjunct Professor in the School of Social Science and Policy at the University of New South Wales. He has written two books* and published more than 150 articles on aspects of crime and about criminal research