Weisbrot

You can download a PDF version of this article here

The Australian Law Reform Commission got engaged in this work at the end of 2000. At that stage, I hadn’t studied any science – unless you count political science – for about 30 years, not since my first year compulsory courses in biology and physics. But on a day in August there was a report on the front page of the Sydney Morning Herald and The Age resulting from a study by Associate Professor Kristine Barlow-Stewart, a noted genetic counsellor – Australia’s first and best genetic counsellor, and a postgraduate law student at the University of Melbourne.

They had surveyed genetic support groups like the Huntington’s Association and the Cystic Fibrosis Association, and asked, “Have you ever suffered discrimination on the basis of your genetic status?” About 100 people answered, “Yes.” Most instances were in the insurance area, about a third in employment, and then a grab-bag related to the provision of government services and so on.

I got a call that night at home from the then Federal Attorney-General, Daryl Williams. As he was ringing from Perth, it was really late in Sydney, but I was excited by the call. He asked if I had read the story in the paper. I said I had, because it had an understated headline, something like Brave New World is here, or Gattaca has arrived in Australia. He asked if I would like to work on that. I said, “I would love to, it sounds fascinating.”

I was in the shower the next morning when he was announcing it on the AM radio program. I found, over the 10 years at the ALRC, that the wheels of government often spin very slowly; but on that occasion, they moved very fast and we were pleased to begin work.

A world first

Although there is a fair bit of concern around the world, the ALRC was the first to take a big broad, comprehensive look at all the ethical, legal and social implications of genetic testing and information. So the final report, Essentially Yours, has been remarkably influential all around the world – even in countries where the detail might not be that relevant because their medical delivery services or health care systems are different or their discrimination laws are different. But the report at least provides a checklist for every country to go through the key issues.

Genetic testing has been around a long time

Genetic testing has been happening for a long time. For well over 100 years, insurance companies, in doing their underwriting, have been asking about family medical history. They have known for a long time that familial health is a key predictor of individual health.

Since about the 1960s, there has been comprehensive neonatal testing, the so-called ‘Guthrie tests‘, organised a little differently – as is the Australian fashion – in each state and territory. They test for diseases such as cystic fibrosis, but even more directly, for phenylketonuria (PKU) and galactosaemia, which parents need to know about immediately in order to alter their child’s diet or other care.

There is now a whole range of issues around neonatal testing that we are only starting to think about. I don’t remember these tests being done on my kids, who were born in 1985 and 1991, but my wife, who should have been in less good a state of mind to remember, nevertheless does remember that very clearly. I don’t remember anyone coming in and saying, “Here is a consent form, here is what we are doing.” The situation is much better now. There are good informative brochures given to people and there is much more care about explaining the nature and value of that kind of testing. But just to make that point: genetic testing has been going on for a fair while in this particular context, but is now much more widespread and sophisticated.

The human genome

Modern consciousness about the power and promise of genetics is about a decade old.

It is nearly, to the day, ten years since that big moment on 26 June 2000 when Bill Clinton, Tony Blair (by video link) and the two main scientists involved, Dr Francis Collins on the right, who headed up the National Human Genome Research Institute, one of the National Institutes of Health in the US, and Dr Craig Venter on the other side, who headed the private company, Celera, were in a neck-and-neck race for a long time to see who would do the first full sequencing of the human genome. There are some good books (for example, by Matt Ridley and Kevin Davies) available that talk about all the cloak and dagger that went on. Eventually Tony Blair and Bill Clinton decided to harness it together and have this big public announcement in 2000. That really brought it to public attention. (Collins, in fact, came out of retirement, just half a year ago – at President Obama’s request – to head up the whole National Institutes of Health.)

The ALRC’s national enquiry

During the Australian Law Reform Commission’s major national consultation, we held 17 big public forums around Australia. We had nearly 300 meetings with professional and community groups and other stakeholders. We found that there were really two kinds of views, often held simultaneously. On the one hand, there is the huge promise of genetic medicine: truly personalised medicine, the beginnings of regenerative medicine, and the use of genetic medicine for better diagnosis and to develop new or better cures.

Then there is the other side, the dark side of a geneticised future. The film Gattaca didn’t seem to do that well at the box office when it was released as a feature film, but every Australian we came across, the tens of thousands over so many years, seemed to have seen the film in which Ethan Hawke wants to be an astronaut.

That had been his dream since childhood. But, of course, to go into space for years and years you have to have ‘the perfect genome’, which he didn’t have. He had some genetic predispositions to some kinds of diseases. As Judy Kirk mentioned, there would hardly be a human who didn’t. But the lead character manages to find some kind of lazy, dissolute and cynical person who has the perfect genome but no motivation. He gets that person’s DNA and secretes it on his body so that he can pass the tests to show that he has those attributes. People are becoming concerned about whether that is what our society is going to become – one in which ‘DNA is destiny’.

The national inquiry, held jointly by the ALRC and the Australian Health Ethics Committee of the NHMRC, ran for about two years. There were some fairly simple terms of reference in relation to human genetic information or the tissue samples from which that information can now be very readily and increasingly inexpensively derived. How do we best:

– protect privacy interests,

– protect again unfair discrimination, and

– ensure the highest ethical standards.

These key concerns were carried across the whole project, and applied to a wide range of contexts.

Discrimination law is a bit tautological – there are some distinctions we readily allow. To get into Medicine or Law at university you have to have a very high TER. We say that it is fair to distinguish amongst certain individuals whether or not they will get into that program; similarly, to select an athletics team, we choose people who can run faster than others and have a chance to win. So certain sorts of distinctions or discriminations are lawful; and others sorts we find invidious – I will come back to that. Finally, we have to ensure that we have the highest possible ethical standards across clinical practice, medical research and a whole range of other areas.

Privacy, unfair discrimination and high ethical standards

We then looked across the growing array of contexts to which those issues could apply: privacy, discrimination, and ethical standards. We got together to brainstorm at the ALRC offices many of Australia’s leading geneticists, people being talked about as potential Nobel Prize winners, genetic counsellors, clinicians, researchers, Human Rights Commissioners, Privacy Commissioners and many, many others. We asked: “What we should be looking at, not just over the next few years, but what are going to be the issues over the next 10 years and the next 20 years?” Interestingly, without exception, every single issue we brainstormed – including the ones that we thought would happen in the next 10 or 20 years, or maybe not in our lifetime but in the future – every single one cropped up during the two years that the inquiry ran. This is a very rapidly moving area.

In relation to variety of circumstances we considered, running down the left of the slide in red are the things which occur on the medical side. For example, in the delivery of clinical genetic services, looking at systemic health care issues, how do we prepare the Australian health care system for this increasing power that genetic testing and information brings? How do we ensure that we have sufficient clinical geneticists, that we have the right lab equipment, that we have enough genetic counsellors to go around, and so on?

Then we looked at some emerging issues both for research and clinical work: the increasing accumulation of human genetic databases, tissue banks and registers, such as the one which Judy Kirk runs, the cancer registry. In fact, those became quite important, not only the outstanding organisation Judy runs at Westmead, but others around the country, like Graham Suthers’s operation in South Australia, where they were doing really important work which really cut across both the importance of good solid genetic work in a technical sense, but which also raised a host of these ethical, legal and social issues.

Employers’ access

Down the right side of the slide, in black, are the non-health and medical things you might not ordinarily associate with ‘genetics’. These matters came out a little in Judy Kirk’s presentation. To what extent should employers have access to your genetic records, to your genetic information? Can they demand a genetic test? I will get to some of those things in a moment. For example, some employers might say, and there is a case in the US, “We have a very high rate of worker’s compensation and sick leave, can we have a genetic test to see if we can reduce our costs?” It might be paternalistic, or the more positive way of phrasing that, “We run a beryllium mine and there are people with a genetic susceptibility to this; and even if we do all the good occupational health and safety things, these people will get sick unless we know – so should we do genetic screening of all potential employees to keep them out of harm’s way?” And so on.

Insurers’ access

Insurance is a key area. It was one of the big drivers for reform in the US, although there it was mainly in relation to health insurance. Over the last year, we have seen big battles in the US because of the lack of a comprehensive health care system, because of the unaffordability of a lot of health insurance in the US, and the fact that about 30-40 percent of the population had no or very limited access to health care or health insurance. That became a big battle there. In Australia it is very different. I will get back to that later.

Forensics

Almost every television show now seems to be about police using DNA to solve a crime. And, indeed, law enforcement authorities in Australia are now quite comfortable with the forensic use of DNA.

Kinship and identity

We might not ordinarily think about kinship and identity issues, but we found that the Australian Department of Immigration (it has changed its name several times and is now the Department of Immigration and Citizenship), doesn’t normally require genetic tests for family reunion migration. But if you cannot provide the normal records which they would like to see – if you come from a country where there aren’t those records, or where there has been war or devastation and you can’t get those documents – but you say, “She is my aunty and is sponsoring me, I am genuinely her nephew although I can’t prove it with other documents”, they will allow you to come forward with a genetic test to show that you are indeed the child or nephew or other close relation of the person sponsoring your migration.

Paternity

Passions and concerns about parentage or paternity testing featured to a much greater extent in the inquiry that we had anticipated. A large number of submissions we received came from fathers’ groups, who argued that fathers or putative fathers should be able to test their children or putative children, without the child’s knowledge or the knowledge of the other parent, and to do so using non-accredited labs. We said, simply, “No” to both propositions. A whole range of ethical issues arise in relation to DNA paternity testing – a much more powerful and conclusive technology than blood-typing. Should you require the consent of the child, if he or she is of sufficient age to understand the circumstances and provide informed consent? What about the consent of the other parent? Should the Family Court be involved, to determine and protect the ‘best interests of the child’, or can this be done privately by agreement? What sort of counseling – genetic, family, psychological – should be made available? And so on.

Ethnicity and Aboriginality

During the course of our inquiry, an election was being held for ATSIC (which no longer exists but has been replaced recently by another Aboriginal self-determination body). An activist in Tasmania systematically objected to 800 people on the local roll of ATSIC electors. He said, basically: “I know you, we’re part of a small community. We’ve grown up together. You’ve never identified as Aboriginal previously. Suddenly, because it has become interesting, or glamorous, or culturally fashionable, you are now identifying as Aboriginal. But I don’t believe that you are, or should be allowed to identify yourself in this way.”

Some of those people objected to went to the Federal Court and said, for example, “Here’s an official document from 1898 to say that this woman is identified conclusively as an Aboriginal woman, and I can show, through DNA testing, lines of descent to that woman.” Does it make somebody Aboriginal to have their DNA confirmed? Does a DNA link confer ethnic or racial identity? The legal test we have tended to use in relation to Aboriginality has been: (a) self-identification with the community and (b) recognition by the community of that person’s cultural identify. But could you do it exclusively through DNA? The ALRC was very uncomfortable with this, and thought that these sorts of issues required further thought and consultation, especially within the Indigenous community.

Other rights and services

Three areas which came up as hypotheticals in the brainstorming actually resulted in real cases here or overseas during the life of the ALRC inquiry: for example, can a private school say, “We would love to have Johnny, but that terrible Y-chromosome is causing us all of these problems and we have a lot of boys with ADHD, so we would like a genetic test to see if he has a predisposition to ADHD.” Or in aged care, “Yes, we would love to take your grandmother, but it is so much more expensive to have someone with early onset Alzheimer’s, so we would like a genetic test to say that she doesn’t have the markers for that.”

Sporting associations increasingly use medical and genetic testing for a wide range of things. At one stage, we phoned the Australian Institute of Sport because we knew they are state of the art world-wide when it comes to all sorts of medical testing. We asked if they do any genetic testing. They said, “We do some. We’ve got state of the art facilities, world-wide.” We asked if they had a protocol which looks at the privacy and discrimination issues in the testing of children, because a lot of people there are quite young – gymnasts especially – but in other sports as well. There was a long pause on the other end of the phone. To their credit, they didn’t fudge it or make it up, they said, “Oh dear! You are right, we need a good protocol to cover these issues.” And indeed, the AIS set up a committee, on which I served, to establish a protocol for the ethical use of genetic testing and information in sport. That protocol was approved by the AIS, and then the parent body, the Australian Sports Commission. The World Anti-Doping Agency is now looking at using that protocol as a model, setting it as the standard world-wide. It is really a good piece of work.

In the ALRC’s final report, Essentially Yours, produced in 2003, we made 144 recommendations. About two years later, the Howard Government responded, accepting more than 90% of them-and we were delighted by this. I guess an indication of the spread or the dispersal of genetic information, the variety of contexts in which it emerges, was the fact that our recommendations were not merely directed to the Federal Government to amend legislation – although there are a fair few recommendations in that respect – but the recommendations are directed to 31 different actors, including states and territories, various regulators, health professionals, insurers, employers, trade unions, police, medical schools and a host of others.

Francis Collins, who as I mentioned before, had headed up the whole Human Genome Project, was a keynote speaker at the 2005 World Genetics Congress, which is held every five years. I had no idea that he was aware of the ALRC report. He pulled it out from under the lectern, waved it around and described it as “a truly phenomenal job, placing Australia ahead of what the rest of the world is doing.” Sometimes we are actually good at doing this kind of public policy-making in Australia. In this instance, what we tried to convince the Government of, with reasonable success, was that it is much better to lay down good policy in advance than to crisis-manage problems later, which might compromise the quality of the scientific and medical work we do.

Australia does outstanding biotech work. Depending on which study you read, we are either 6th or 7th in the world in terms of biotech innovation- a long way from the much larger US perhaps, but in among a cluster of other high tech countries, like Japan France, Korea and now China. We want to make sure that this innovative work is all done in an environment in which the general community feels that privacy and unfair discrimination are protected and that ethical standards are maintained at a high level.

A Human Genetics Commission/Advisory Committee

A key recommendation in the ALRC report was that this area is changing so fast that to keep up with regulating it effectively in the public interest, the government needed to set up a standing Human Genetics Commission or Advisory Committee. In fact, it has set up the Human Genetics Advisory Committee of the NHMRC, a new principal committee of the NHMRC. This comprises people who work directly as clinical geneticists and researchers, lawyers, privacy people, community members and so on.

Adaptation of anti-discrimination laws

The ALRC report recommended amendment of Australian anti-discrimination laws to provide protection against unfair discrimination based on real or perceived genetic status. These were among the 90% of recommendations accepted by the Federal Government in 2005. It took a little longer to get formal implementation, but the Disability Discrimination Act has been amended expressly to cover genetic discrimination. Since August 2009, the Disability Discrimination Act provides, basically, that you can’t use predictive genetic information to discriminate in employment, the delivery of services and other areas. This extends to information derived from a genetic test or otherwise, and covers adverse decisions based upon ‘perceived genetics status’ – such as treating someone from a Huntington’s family as if they have Huntington’s, whether or not they personally have the condition or have the genetic markers for that disease.

Adaptation of privacy laws

A key privacy issue in this inquiry was about the handling of shared information – by definition, genetic information is shared with other family members, and sometimes with a whole community. Judy Kirk’s family tree and case study was a perfect example of this. We spent a lot of time talking to the familial cancer registries, who said that there were several key problems in doing their work effectively. How do we safeguard the privacy of others when we take a family history from our patient? Can we go and ask the patient’s relatives about medical history or their genetic status?

The Privacy Commissioner has now granted a public interest exemption for doctors to be able to ask about family members. Strictly speaking, when an individual sits in the doctor’s office and is asked, “What is the health status of your family? Does anybody have problems with cancer or heart disease or diabetes?” and information is collected and stored about this aunty and that uncle and my brother, the recording of that information about others would be a technical violation of the Privacy Act. But because it is so obviously what we should be doing to provide effective healthcare, and is so routinely done, there is now a formal exemption for that kind of work.

Apart from collection, there is also the question about the dissemination of shared genetic information. For hundreds of years, based on the Hippocratic oath and western traditions, we have said there is a primacy on the confidentiality of the doctor patient-relationship and that you shouldn’t go beyond that. What happens in the situation where you know that a serious genetic condition is running through a family, such as colorectal cancer or breast cancer, or familial adenomatous polyposis? Judy Kirk says to the people, “Here is some literature; you really should tell all your sisters and brothers and other close relatives to come in and get screened themselves.” Unfortunately, however, we have heard the story too many times, of people saying, “I am really not comfortable with that, I have not told anybody that I have cancer. I am embarrassed about it and I don’t want to do that” or, worse, “My sister? I hope she gets cancer; ever since that horrible Christmas we haven’t spoken”-and you then have a pretty good idea that they are not going to share that information with their close relatives.

A number of those running these registries told us that, “We live in fear of the phone call that comes from the sister, who now has advanced breast cancer, who says, ‘I understand that you treated my sister a couple of years ago. You told her to contact me. She didn’t and you probably knew that she wouldn’t. You didn’t make any effort to contact me. If you had done so, I definitely would have gone to my doctor and got screened – and I probably wouldn’t be in this desperate state now.'”

We made a recommendation we believed in, and didn’t think the government would necessarily accept. It was a bit out there. We said that, if the circumstances I mentioned arise, health professionals should be exempted from the restrictions in the Privacy Act and should be allowed to disclose the information to relatives without the consent of their patient. There are already rules allowing that where there is an imminent threat to a person’s health or safety – but genetics is never that imminent – so now if there is a serious genetic risk of harm to the health and well-being of others, then that may be disclosed. That only came into force about a year ago or so, and it will be interesting. Has anyone here had any cases where you have done that?

Professor Kirk: It relates only to private practice and genetics does not occur much in private practice in Australia.

Professor Weisbrot: That is true. It will have a limited application for a while because of the funny way our Privacy Acts are currently organised, with different provisions for the public sector and the private sector, and different laws for the Commonwealth and each state and territory. It is something to keep an eye on, though, as the Commonwealth increasingly takes over the hospital system nationally.

The right not to know

Again this issue came up in Judy Kirk’s scenario, where some relatives say, “That’s not how I live my life. I know there is Huntington’s in the family, but I don’t want to live with that diagnosis hanging over my head.” We heard from one very senior clinical geneticist who has published widely and is a world expert on breast cancer. She didn’t want to have the genetic test for the most common mutations for breast cancer because, as she says, “I know myself and even though it has been a horror throughout my whole family, if I take the test and it shows that I don’t have the markers, if I don’t have any of the BRCa markers, I will relax too much. I will stop doing self-inspection, I will stop getting mammograms. I want to act as if I have the genetic markers and so keep totally aware of this all the time.” There is the full range of human behaviour in this area.

Regulation of genetic testing labs

We recommended that any DNA testing in Australia-except where it is a research lab, but if you are reporting a result for healthcare purposes-should be done only by labs that are fully accredited for this purpose by NATA and the RCPA. Remarkably that wasn’t the case at the time.

Illegal access to genetic material

The ease with which someone else’s DNA may be obtained, and tested, led us to consider the introduction of a new crime for non-consensual DNA testing. Since we are all sloughing off DNA all the time and it is very easy to get someone else’s DNA, and it’s known that former US President Bill Clinton, members of the Royal Family, celebrities and others are very sensitive about this.

The famous case in the US from a few years ago was Burlington Railway. This big railway company felt that absenteeism and worker’s compensation claims based on RSI injuries was costing them a fortune. They felt that they spent a lot of money on training and were not getting the full satisfaction or the full reward from their employees. They set up a program which said something like “Cholesterol checks – free”. They said that they were caring employers and asked for some saliva, blood or tissue to see if their workers had any cholesterol issues. What they were actually doing, however, was junk science of dubious morality: they were really testing their workers to see if they had the genetic markers which supposedly coded for increased risk for RSI. A whistleblower in the company in the human resources department was appalled and leaked it to the US Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, roughly equivalent to our Human Rights Commission. The company was sprung, came in, grovelled and said, “We are terrible, we won’t do it any more, we will compensate the people involved, and we will destroy the records.”

This is a good example of how easy it would be for a private organisation, private investigators or, indeed, government officials, to get people’s DNA and surreptitiously test it. The DNA is readily available, the cost of testing is plummeting, and there will be financial or other incentives to pursue this-unless we put a stop to it.

Even though I’ve spent most of my career as a policy-maker desperately trying to avoid the use of criminal law in regulation, we felt so strongly about this that we recommended that laws be brought in federally and in the states and territories which would make it a crime to (a) take someone’s DNA and (b) submit it for testing, (c) without their consent or without other lawful authority – lawful authority being, of course, police officers undertaking forensic testing for authorised law enforcement purposes, or medical and scientific researchers who have ethics committee approval for DNA testing, or someone doing it in pursuant to a court order for a paternity test.

Again, somewhat to our surprise, the Howard Government accepted that recommendation, but unfortunately the Standing Committee of Attorneys-General has not been doing a very good job of bringing that legislation to fruition. In November 2008, a committee of SCAG published a poor quality discussion paper which really misunderstood the genetics. The definitions were much too wide and poorly targeted to the real problems. Consequently, they got a lot of adverse submissions saying “great idea but terrible execution”, and nothing has been heard of it since. I don’t know whether or not they are proposing to have a second crack at it, but I hope so

Direct-to-consumer testing

Another issue which was raised by Judy Kirk earlier was about “do it yourself” or “direct to consumer” DNA testing. This has really come out of nowhere in the last few years to become quite a remarkable phenomenon. The first of these test kits emerged in the UK about seven or eight years ago. You and Your Genes, was marketed by a British company called Sciona. They purported to test nine sites on your DNA and to give you lifestyle advice based upon your personal genetic profile. The kit was initially marketed through The Body Shop and Boots the Chemist. I think it was the London Times which questioned the CEO of Sciona about the test’s value. The CEO was quoted as saying, “Well, there is already a lot of information out there recommending a diet high in fruit, broccoli and grains. Consumers find this advice daunting, as they are not sure to what extent it pertains to them as individuals. So eat well and exercise people find daunting. What they really need is genetic test information.”

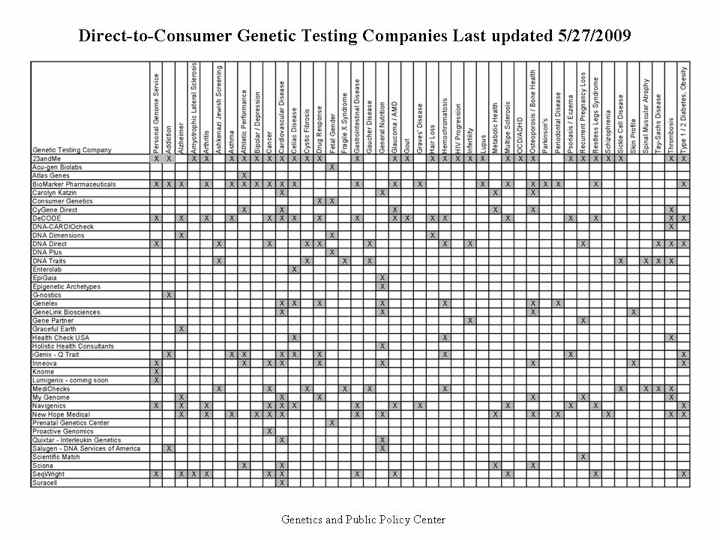

The marketing and provision of genetic testing services directly to consumers has really taken off in recent years, to the extent that in the US, the Secretary of Health’s Advisory Committee on Genetics, Health and Society identified 90 or 100 big issues they thought they had to be looked at seriously – and consumer genetics was ranked number 1 on the list. Here are some reasons why. The Genetics and Public Policy Center in Washington has been keeping track of how many companies offer direct to consumer tests and how many tests there are.

The graphic really makes the point. When I first looked at this table four or five years ago, there were something like three or four labs offering five or six tests. Now there are 40-odd labs and 100 tests. In fact that is not even the latest table available; there is a much more recent one, but it contained 16 pages of Excel spread sheet and I couldn’t figure out a way to put that on a PowerPoint slide. That is how fast it is growing. Some of those tests are just silly, like tests for male pattern baldness. You can look at your grandfather or … you can have a genetic test. However, some of the tests involve quite serious and complex conditions, things like genetic markers for psychiatric illnesses. What is someone supposed to make of this when they get it back in the mail? They do a buccal swab, stick it in a baggie, send it off overseas and it comes back and says that you have a higher than average predisposition to schizophrenia. I find those things very frightening. We don’t know about the quality assurance or the underlying science behind their testing. We don’t know about the security or privacy regimens underpinning it. Because this testing occurs in a direct to consumer environment, without the mediation of the person’s doctor, we don’t know whether people are offered good genetic counseling (presumably by phone), or whether they take up the offer.

Do we need to regulate that more strictly? At the softer end, is there a difference between some of the ‘lifestyle’ genetic tests and mood rings? Is DNA testing the mood ring of the 2010s? My son got a mood ring not long ago, which cost something like $2 at Paddy’s Market. It is always black. He said to me, “Do you think it must be broken or something? It’s not working.” I said, “No, no, you’ve actually made me a believer!”

Here are some of the things that are out there being marketed to consumers.

Dermagenetics. This particular company has since stopped offering this, as far as I know, but they previously had a fantastic commercial. There was the guy in the white coat striding out in his lab; things are whirring all around him – medical equipment, presumably – and he says, “Our scientists have discovered the five wrinkle genes.” So for $250 – and for something so important to human evolution as wrinkling, you would think there would be a lot more than five genes – but anyway for $250, they will give you a test which tells you your particular wrinkle gene pattern and then, for thousands of dollars, they will sell you cosmetics tailored to ‘your particular DNA’.

Nutrigenomics, which I referred to before in relation to Sciona’s promotion in the UK, is exploding as well.

This is a good graphic illustration of what’s going on there. Is ‘your particular DNA’ better suited to a diet rich in oranges or cake? That’s a test that I would like to take. It might give you some ideas. You will pay about $1,000 for that. I don’t know if they throw in the cake.

Personalised Medicine is now portrayed as just being around the corner.

Here is the website of deCODEme, an international testing company, probably most famous for the controversy around its pioneering Icelandic national data base. You can see that what they are saying is that, for about $1,000, they will scan for a million variants which calculate genetic risk for 17 diseases. $1,000. Judy, how much would it cost just to do a BRCA test?

Professor Kirk: One gene costs $1,000.

Professor Weisbrot: Something can’t be right there. The maths just doesn’t work. But that is what they are purporting to do.

This is where I personally find it gets even more scary, where “do-it-yourself genetics” meets Google, literally.

This is 23andMe, a company that was founded by the wife of one of the main founders of Google: she is one of the two principals of 23andMe. They are doing the same thing, ‘unlocking the secrets of DNA’ with 23andMe. Also costs about $1,000 and roughly the same sort of thing is being offered as we saw with deCODEme. But they are much better at marketing than a host of others. They have carved out a whole new niche that I have described as ‘celebrity genomics’. They held a highly publicised ‘spit party’.

This was on the front page of the New York Times a year and a half ago. There is Wendi Murdoch. Rupert was there, but is not pictured. Anne Wojcicki, the wife of one of the Google guys, was there. Barry Diller, a head of Fox Studios, a major entertainment entrepreneur was there. Harvey Weinstein, the leading Hollywood producer and film maker was there. Ivanka Trump was there and so on and on.

You can see that the party was themed Great Expectorations. It was all about “We will go and do this and won’t it be fun? We will have a party and we will find out: maybe I have a predisposition to Parkinson’s and you have one too, or perhaps early onset Alzheimer’s?” It really was marketed in that way. “We will have parties and this will be fascinating information we can share and talk about.”

Shortly after that, the Sydney Morning Herald contained a story about the actress Glenn Close agreeing to have her genes mapped in the name of science… She starts off by saying in the interview “As you probably all know, I come from a family that has lots of mental illness in it.” I didn’t know that and I didn’t particularly want to know that lots of her family suffer from schizophrenia or have serious depression – but she was going to do this for science.

The direct marketers are luring people in like that and not being totally honest with what they are doing with their operation. You just send in your information. Here is the New England Journal of Medicine, which is basically the journal of Harvard Medical School, a high-powered medical journal, asking Linda Avey, who is the other partner in 23andMe, “Wouldn’t it be better if people spent that amount of money and bought a gym membership?” That’s a really good question. Remember, it costs $1,000. She said, and you will be hard pressed to find this approach articulated on their web site, but have a try when you get home: “We totally agree it’s premature. This information isn’t ready for diagnostic purposes or for necessarily taking any kind of action. We are really more about building a new research paradigm. We want to align ourselves with the research community so our customers feel like they are actively engaged in a process.”

What they are effectively doing is building up a private version of the UK’s Biobank, which is getting 500,000 people to volunteer samples altruistically in order to assist medical research – except that 23andMe is doing it privately and making people pay $1,000 for the privilege. It is totally unclear what the governance arrangements are – the independence of the board, the ethics oversight, the privacy protections and so on. If if you drill down about six levels on their web site, it says “We may provide third party organisations access to this information for scientific research”, with more detail about disclosure to ‘research partners’, who will no doubt be looking for breakthroughs to patent and commercialise.

Employment and insurance

As mentioned before in relation to the reform of anti-discrimination laws, the general rule the ALRC proposed was “no use of predictive genetic testing in the workplace”. That has basically been accepted by the government in the amendments which were made to the Disability Discrimination Act recently.

In the insurance area in Australia, unlike the US, we are basically only talking about life insurance and other individually risk-rated products -not private health insurance, which is community rated (that is, where you choose your cover and you pay a designated amount, whether you are 18 or 80). Insurance is a private market, based totally upon risk assessment, so we were loathe to interfere unduly in the market. Recognising the nature of this industry, the Disability Discrimination Act (as well as the Age Discrimination Act and the Sex Discrimination Act -but not the Race Discrimination Act) provides an exemption for insurers to draw distinctions among individuals in the underwriting process, but only to the extent that those decisions are based upon actuarially and scientifically relevant facts. So we did say to the insurers, “You have to lift your game. You have to make sure you are acting only in the most scientifically and actuarially relevant way, in order to keep your exemption under the Disability Discrimination Act. You have to incorporate the latest, cutting edge, thinking in science and medicine; you can’t stereotype or make assumptions based on a label like ‘elevated predisposition’. You have to provide reasons for any adverse underwriting decision, and then you have to provide a no cost or low cost, accessible review mechanism that people can go to when they get an adverse underwriting decision, such as a higher premium or exclusions, much less refusal to offer coverage.”

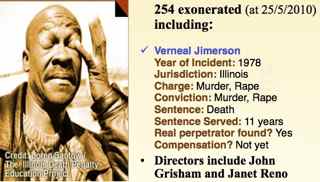

As we are running out of time, I will just mention in passing some other big issues we have not talked about tonight. In relation to forensic DNA testing, which does not involve looking for genetic health markers but rather compiling individual DNA profiles, I think one of the most interesting web sites is The Innocence Project, which now records 254 exonerated people – most of them on death row in the United States. They are using DNA testing to show that, in these cases, the convicted person could not possibly be the person who committed the relevant crime. One of them is pictured there.

Every time I give a presentation I go and check the latest statistics on the website. The list of people exonerated for serious crimes and released from prison – including death row -has gone up from about 150 a couple of years ago, to 254 now. This is important stuff.

Thank you so much for your kind attention.

About Weisbrot

Professor David Weisbrot AM BA(Hons) Queens College New York, JD University of California. He is a Professor of Law and Governance at Macquarie University and Professor of Legal Policy at the US Studies Centre at Sydney University. He is also an Emeritus Professor of Law and an Honorary Professorial Fellow in Medicine at the University of Sydney.

He was President of the Australian Law Reform Commission from 1999 to 2009, where he led major inquiries into, inter alia, the Protection of Human Genetic Information, Gene Patenting and Human Health, and Privacy Law and Practice. He is a member of the Human Genetics Advisory Committee of the NHMRC.

He was awarded a Centenary Medal by the Australian Government in 2003 for ‘services to law reform’, and made a Member of the Order of Australia in 2006 for service to the law and other areas of legal interest. He recently received the NHMRC’s award for most outstanding contribution to health and medical research.